I am not a professional in etymology or linguistics or languages overall…BUT we did manage to afford the Compact OED* way, way, WAY back when it was new(ish) and used to use it for (among many other things including research) playing Scrabble with friends. OED Scrabble was a lot of fun, if slow enough to […] [...more]

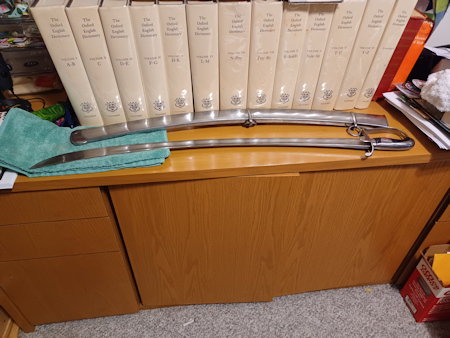

I am not a professional in etymology or linguistics or languages overall…BUT we did manage to afford the Compact OED* way, way, WAY back when it was new(ish) and used to use it for (among many other things including research) playing Scrabble with friends. OED Scrabble was a lot of fun, if slow enough to allow two people to play chess on the side. And back in those days I could read the OED without a magnifying glass or glasses by putting my nose maybe half a centimeter above the paper, at which point the tiny print was in focus. ANYway. I now need reading glasses and the magnifying glass that came with the set.

*OED Oxford English Dictionary. I always yearned to own the full version but it was and undoubtedly is still, incredibly expensive in its full expanse.**

** I had to look it up. 20 volumes, 4 feet of shelf space, $1,215 from Amazon. That’s new. What have I got I could discard to gain four feet of shelf space? There’s not another place in the house to put another bookshelf. Certainly not the 2013 Britannica. Or the 1950 Britannica. Not any of the nonfiction; that’s my personal research library. (Looking with narrowed eyes at the fiction shelves. How much of that am I going to re-read? Yes, it’s also reference, but…I have just be attacked by a massive lump of book hunger. And older, not up to date ones aren’t as expensive…there’s a lovely earlier 13 volume version, about what I remember from college. Used, yes, but very nice, with proper volume covers…YUM.) Writers need words. They need to *understand* words, in the depth of time those words have been used. They need words sitting around them, emitting all the nuances…filling their heads with words…beautiful, sensual, luscious, practically chewable, words.

Yesterday, in conversation with my agent, who had had someone else look at the Horngard ms., it turns out the first question to be answered, from the third person was “What is a paladin?” because all that cane immediately to his mind was Dungeons and Dragons paladins and even a cursory reading on Horngard revealed that nobody in *that* book thought of paladins the way whatisname did (sorry, but the head injuries are playing serious games with name memory today. I can clearly remember the stuff in the rule books that so infuriated me about the abuse of the paladin concept, but not the name of the man who wrote them…wait…Gary. Gary something…starts with G also. Not Geronimo, shorter than that. Gorgon, Griffin, Grimaldi….Gary-Gary-Gary…yes, this is a problem.) By chewing on the old problem of “Why on earth did you write rules that made “lawful good” essentially include “stupid” and why did you let people start at level zero as paladins (and stupid-good) when the actual paladins (there were some) were all experienced and expert fighters?? I was then motivated to go haul out the second (heavy!!) volume of the compact OED and look up the history of the word and see if I’d remembered any of that.

I’d remembered it wrong, OK? But here’s the straight scoop from the Compact OED. It goes back to Charlemagne’s court. Now remember–this is post-Western Roman Empire time and Europe was mostly a seething (thinly seething) mass of little realms–Charlemagne (just means Charles the Great) of the Carolingean dynasty (became king of the Franks in 768,, King of the Lombards from 774, and was crowned as the Emperor of the Romans by the Pope Leo III in 800, and died in 814.) I regard those dates as…iffy, because of later calendar changes and I don’t know how much slippage was accounted for, but I could be wrong. 8th to 9th century Common Era, anyway. Who were the Franks and the Lombards? Funny you should ask. They *had* been among the invaders who toppled the Western Empire, handily tucked into one or more of the Goths & Vandals tribes. I happen to have a translation of the Lombard Laws from a pre-Charlemagne period, (like the Burgundian Code I also have a translation of, both of these researched and done by my medieval history prof, Katharine Fischer Drew, then chair of the History Department of Rice University, may her name be remembered for good scholarship AND being a really good history teacher and administrator. Both of those legal codes were intentionally modeled on their view of Roman Law (the first codified law either bunch of barbarians had ever seen) but the difference between the stately and determinedly “universal” approach of the Romans and the decidedly particular and individual approach of these Germanic tribes is both notable and useful to fiction writers wanting to add a little verisimilitude to their sometimes unconvincing narratives.

Back to Charlemagne. Because Pope Leo III, wanted to recreate a more stable and uniform Europe (e.g. the Roman Empire), with Roman Catholics in charge and no more Byzantine invasions and persecutions, he gave Charlemagne the title of Emperor of the Romans, although the actual crowning ceremony occurred in what is now France, not in Rome (Leo III had fled Rome. It’s a really *lively* period of history which makes clear that interesting times may be interesting but get a lot of people killed, displaced, and wishing for nice boring peace for long enough to raise a family. Some people are never satisfied–or rather, in any situation some want it to last and some want to change it. Charlemagne’s father was Pippin (not Tolkein’s Pippin); that’s how Charlemagne inherited the crown of the Franks; his brother had the Lombards but when his brother died, Charlemagne just snagged that crown, ignoring his brother’s heirs. Nice fellow. As you can imagine, becoming and staying king, and gaining more meant wars and so Charlemagne as a feudal sovereign had fighting men–good ones, or else–under him. Specifically twelve peers, who were “of the palace” (hence, through a couple of spelling wiggles, paladins, “palace warriors” the paladin title meant, who were directly sworn to him.

From Charlemagne’s court, the term spread with bards, writers, etc. and was helped along by Chretien de Troyes and his tale of Arthur and his Round Table and others. Suddenly the Matter of Britain got involved. Then the courtly romances of somewhat later medieval times. Various other attributes got tacked on to the requirements for paladins (being polite to women, being clean, being pious. The “parfit gentil knight” thing. Galahad, not Lancelot. Oh, and of course the Chanson de Roland was part of it, and even the Welsh poet Taliessin. In German mythology, as expressed in Wagner’s operas and their preceding legends, the perfect knight might be tangled in pre-Christian mythologies as well. The term was sometimes used for the exceptionally brave alone but more often for a cluster that included “presentable at a palace” (so the bravest soldier in the army, a terrific fighter, if too rough and cruel…couldn’t be a paladin. Looking at Charlemagne’s time, this must have been a later addition.) Courage, fighting ability, courtesy. Often righting wrongs on his own, a knight errant off doing great things. Since the Holy Roman Empire included most of Europe at one point, it also included staying within the bounds of Holy Roman Catholicism, and included Spain-to-Germania. Not, however, Scandinavia. Vikings were immune to the romantic nature of paladins, until later.

My first experience with the word was in stories *about* the middle ages, the knights in shining armor approach. But a degree in history, most of it ancient & medieval, gave it a lot more dimension…[[Gygax. That was the guy’s name. FINALLY. Gary Gygax. OK, sorry I couldn’t remember it faster. The memory isn’t totally gone, it just has an extremely slow name-finding function.]] Besides Dungeons & Dragons (before that arrived, in fact) but after writers like Scott & Tennyson & the spate of Arthurean fiction that popped up at intervals, there was a TV series called “Have Gun, Will Travel” with a main character names Paladin. He wore black, carried a gun, shot people, and usually in the course of an episode, righted some wrong or other. Modern paladin that sort of, but didn’t entirely, sit right with me when I watched it. Like an unromantic Zorro (yes, I watched that one too.)

Paksworld paladins are based on the older form, as most of you know. However, the intrusion of functional magic in various forms in Paksworld allows paladins to do things that Charlemagne’s palace warriors could not. Keeping their powers limited and sufficiently different from the magicks of others felt necessary to me, though the ability to light a fire or even a candle from a finger almost tempted me to give paladins “ordinary” magelight. Nope. Paks & others get the bright white “reveals the truth” kind of light. What else? They can’t be fooled when it comes to good/evil or truth/lies. They have an innate ability to heal–it’s from their patron saint or a god, and it goes beyond what a Marshal can do. They can protect others from magical fear (an evil projection from some evil source). They are charismatic–natural leaders, and leaders for good. But also they have the skills of expert warriors, including tactical skills developed from years of training & experience. They are courteous, “presentable at court.” They are typically active as paladins alone, going out on quests to accomplish an assignment (right a wrong, find a missing king, stop something bad) though they may associate with a crowd trying to do the same thing. They’re no all alike, and they don’t feel allegiance to exactly the same good powers. Paks and Dorrin, for instance, came from very different backgrounds (as did Gird and Falk). Aris and Seri, the two young paladin figures in Liar’s Oath, one of them born Old Human and one of them born magelord, leading the most vulnerable people of Luap’s kingdom down-canyon and away, hoping to get them back to Fintha…were fully paladins and connected to the old high gods of Old Aare, Sunlord and Sealord and Windlord. They had known Gird personally…they were “his children” nonbiologically but not “his” paladins.

It’s all perfectly clear now, right? My rough-and-ready telling here didn’t buck you off into the mud, did it?